[Originally published in OnSite Review 46]

Has anyone ever noticed how often the word visitor is used by architecture students and practitioners when referring to the human subject of a design project? As in: “the visitor enters the building here…” or “this is a space where the visitors…” It is of course not at all inappropriate to use visitor when the project in question is a museum, but the V-word is also used frequently when discussing residential projects. It’s as if the primary task of architecture were to impress onlookers. Why is it that, in our collective unconscious, the visitor is today’s ideal subject of architecture? Is the impermanence and transitoriness of the Deleuzian nomad fundamentally preferable to the rootedness of the Heideggerian dweller when it comes to architecture?

To begin with, human travel of some sort or other is always necessary when interacting with buildings; their immobility requires us to travel to them. And when we travel to unfamiliar territory, we tend to be much more perceptive to our surroundings than when we are in our everyday environment, which tends to be taken for granted. Travel thus ultimately makes us much more sensitive to architecture, an art that values exceptionality and extraordinariness. As travellers, moreover, we inhabit space transitorily and impermanently, which liberates architecture from the pesky and often mundane demands of regular, everyday users. It would certainly seem, then, that architecture and tourists are ideally suited for one another; a marriage made in heaven. What could possibly go wrong?

This must have been what the political leaders of Barcelona were thinking during the late 1970s and 80s, when democracy was returning to Spain and Barceloneses wanted nothing more than to turn a proverbial page after four decades of repressive dictatorial rule by General Franco. La Barcelona grisa (grey Barcelona as it was referred to then) needed to be transformed into something radically bright and new, and what better means to achieve this than hosting an Olympic Games to kick-start a metropolitan transformation from grimy industrial port to chic and glam tourist destination?

Up to the 1980s, Barcelona was still an industrial city. Factories and smokestacks were everywhere, the city was covered in soot, and shantytowns occupied the city’s beaches and steep hillsides. The only tourists to be seen in the city before the 1992 Olympics were hippie backpackers and camera-clad Japanese aficionados of Gaudí, an architect who had fallen into relative obscurity since the rise of rationalist modernism. Gaudí’s heyday was in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when industry represented progress, and Barcelona proudly referred to itself as ‘the Manchester of the south’. The city held two international expositions during that period, one in 1888 and another in 1929, mainly to promote the latest industrial and architectural trends to the business and political elite. Mass tourism was not a thing in Spain until the 1960s, and then it was mainly of the sun, surf and sangría kind; not urban tourism. The elimination of trade barriers by Reagan and Thatcher in the early 1980s and the subsequent rise of globalisation finally shut down many of Barcelona’s factories, bringing to an end its industrial century. It was time to implement another economic activity.

Today Barcelona is one of the most recognisable urban brands in the world, attracting over 12 million visitors annually. Whenever visiting tourists are asked in surveys what attracted them to Barcelona, 90% of respondents answer ‘the city’s architecture’, by which they really mean the work of Antoni Gaudí and his contemporaries. The rising popularity of Postmodern architecture in the 1980s led to the rediscovery of Gaudí. As a glimpse into any Barcelona souvenir shop will prove, Gaudí is the city’s main attraction, right up there with FC Barcelona. His exuberant buildings, which please crowds from every corner of the globe, made Barcelona into a busy destination for architectural tourism.

Gaudí’s buildings, many of them residential, had to be restored and adapted for reuse as museum quality tourist attractions, a lengthy process that began in the late 1980s. Since then, visitor numbers to Gaudí sites have increased exponentially year after year. Casa Milà, the last project to be completed by Gaudí in his lifetime (Sagrada Família is still incomplete), was transformed from a soot-covered apartment building with neon signs advertising a groundfloor shopping arcade into a museum with prestige office space to let. Bachelor pads that had been built in the attic in the 1960s by the architect Francisco Juan Barba Corsini were ripped out as part of the restoration effort; the attic now transformed into an exhibition space of models and furniture by Gaudí. Buildings by Modernista architects Lluís Domènech i Montaner and Josep Puig i Cadafalch were also renovated and transformed, and the German Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe and Lily Reich for the 1929 International Exposition was entirely reconstructed, opening in 1986.

Barcelona’s rapidly growing architectural tourism eventually led its political and business leaders to pursue another program that would build, literally and figuratively, upon this success; a program which we could call ‘touristic architecture’. If there is such a growing demand to visit historic buildings that were never originally intended for tourists, then why not complement that with spectacular new works of architecture constructed as tourist attractions from the very outset?

Indeed, the reconstruction of the German Pavilion from 1983 to 1986 by architects Ignasi de Solà Morales, Cristian Cirici and Fernando Ramos, working for Barcelona City Council, can be seen as a project that straddles both architectural tourism and touristic architecture. The original pavilion had long been demolished, having stood for only a year; it nevertheless acquired a certain mythical status thanks to the circulation in print media of a series of grainy black and white photographs. The Barcelona Pavilion is one of only a handful of Modernist buildings to be entirely rebuilt from scratch for no other reason than its significance in architectural history. Whereas the original pavilion was designed as a temporary stand for an exposition, the reconstruction was designed to last over a century. The Barcelona Pavilion that stands today was moreover built as a tourist attraction. It was of course also an important reconstruction project of architectural-historical interest, but cultural tourism and the display of art history always go hand-in-hand. Indeed, even the original 1929 German pavilion was a tourist attraction of sorts: it was built for a world exposition with the intention of burnishing the image of post-WWI Germany. Officially, it is no longer called the German or the Barcelona Pavilion, but rather Pavelló Mies van der Rohe, in honour of the architect of the original structure.

Barcelona’s architectural tourism sites consist of historic works. Some, such as the Cathedral or the basilica of Santa María del Mar have not changed use but nevertheless charge tourists nominal admission fees. Medieval Catalan Civil Gothic structures such as the Saló del Tinell or the Drassanes shipyard have been converted into museums; the City History Museum and the Maritime Museum respectively. The Modernista Art Nouveau era is represented by seven works by Gaudí (Palau Güell, Cripta Güell, Park Güell, Casa Viçens, Casa Batlló, La Pedrera, and the yet to be completed expiatory temple of La Sagrada Família), three by Lluís Domènech i Montaner (Casa Morera, Hospital Sant Pau, and Palau de la Música Catalana) and three by Josep Puig i Cadafalch (Casa de les Puntxes, CaixaForum, and Casa Amatller); works that underwent extensive restoration and adaptation.

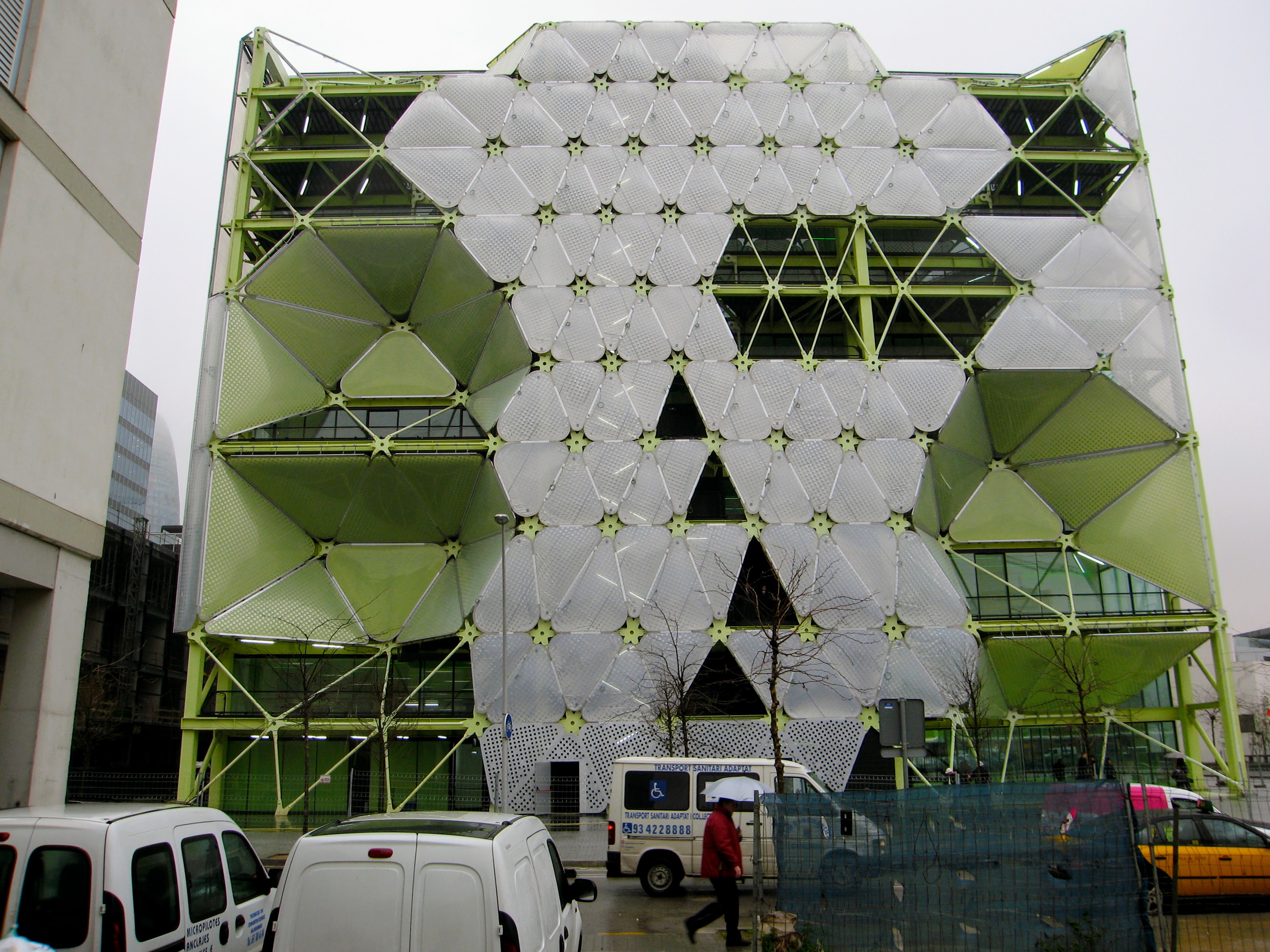

Barcelona’s touristic architecture, by contrast, consists of newly built works with tourism as their main program. These include, in addition to the already mentioned Pavelló Mies van der Rohe, the 1992 Olympic telecommunications tower by Norman Foster and the 2006 Glòries Tower by Jean Nouvel, two full-fledged tourist attractions requiring admission tickets. Other examples of touristic architecture are more subtly masked as museums or public markets, examples of which include the MACBA contemporary art museum by Richard Meier (1995), the Forum building by Herzog & de Meuron (2004), the Santa Caterina Market by EMBT (2006), the Design Museum of Barcelona by MBM (2008), Barcelona’s iconic flea market by B720 (2010), the Barcelona Film Institute by MAP (2010), and the bizarre MediaTIC office building by Cloud 9 (2010). These are all freestanding structures contrasting materially and formally with their surroundings, and often prominently sited at the ends of visual axes while featuring larger than usual public spaces to maximise visibility and handle tourist hordes.

It is one thing, of course, to capitalise on existing (or once existent) heritage, and quite another to build future or predestined heritage anew. In his writings on the preservation of architectural heritage, Rem Koolhaas remarks: ‘through preservation’s ever-increasing ambitions, the time lag between new construction and the imperative to preserve has collapsed from two thousand years to almost nothing. From retrospective, preservation will soon become prospective’.

Touristic architecture is an important component of today’s experience economy, in which non-material experiences rather than material goods are marketed. In an age in which consumers have already acquired an excess of material possessions, experiences are a growing focus of economic growth in which travel features prominently. Indeed, even many material goods – especially automobiles – are today marketed as experiences more than products.

Before the invention of package holidays and mass-tourism, travel was a much more elite affair limited to the upper classes. It was the labour struggles of the early twentieth century that led to the adoption of weekends and holidays for all to enjoy. Is touristic architecture then a similar democratisation of architecture? It certainly offers up a novel form of architectural consumption; one that is affordable to most: the Barcelona Pavilion can be experienced for merely 8 €, the cost of a regular admission ticket.

While touristic architecture erodes some of the elitism and snobbery often associated with architecture, in Barcelona it has contributed to the problem of over-tourism, which puts added strain on infrastructure while transforming the city’s commercial landscape, not to mention causing rents to rise very steeply. Barcelona’s many municipal markets, for example, were once known for selling the freshest foodstuffs, but today many are focused on ready-to-eat foods, a reflection of how businesses have veered toward the more profitable tourism market. The same thing with housing: short-term accommodation is ever more abundant while long-term rentals are in ever shorter supply. The rise in the cost of living has forced working and middle classes to move out of the city, leaving a city centre increasingly devoid of the everyday urban life it once had.

Right: Glòries Tower, Jean Nouvel, 2005.

It’s not just the private sector that caters to tourists before citizens. Barcelona’s current supposedly socialist city council is hell-bent on expanding the airport and hosting ever-more international events to promote Barcelona as a destination. There is a growing perception that planning decisions respond to the needs of the tourism industry rather than those of the local population. The city’s planning department has even developed a tourism dispersal strategy whereby new touristic architecture projects sited in disadvantaged outlying areas would take pressure off the overcrowded neighbourhoods containing tourist sites. City Council even began to promote visiting peripheral working class neighbourhoods as more authentic urban experiences.

But the worst thing about touristic architecture is how outdated and cringe-worthy it appears today. The buildings reek of having tried too hard to impress and outdo one another. There is moreover no common thread between them other than their effort at being unique and contrasting sharply with tradition. Wherever several works of touristic architecture are clustered closely together, such as at Plaça de les Glories (a former manufacturing district converted into a media district in the 2000s), the result is a hodgepodge; an authentic clusterfuck, an architectural disaster area marketed as the new and modern Barcelona; and tourists eat it up like freeze-dried paella on Las Ramblas. This in a city that only a decade and a half earlier won a RIBA Gold Medal for its Olympic-era urban projects.

In the context of today’s climate-emergency, touristic architecture comes across as a big part of the problem, as what largely got us into this mess today. Their structural gymnastics, often involving immense rhetorical cantilevers, consume much more concrete and steel than would otherwise be necessary. The idea of an economy of means, or beauty coming from simplicity, went completely amiss in this period of excess. The only redeeming quality of touristic architecture is serving as examples for how not to design.

Barcelona’s successful tourism industry, built largely on an architectural foundation, has come increasingly under fire in recent years. Demonstrations demanding the degrowth of tourism are a regular occurrence, as is anti-tourism graffiti and even the dousing of tourists by watergun-wielding locals. There are now few places left in the city where locals can get away from tourist hordes. Indeed, one of the reasons Barcelonians are themselves travelling out of town more than ever is to escape from their over-touristified city: tourism as an antidote to tourism. Meanwhile, touristic architecture has travelled abroad as well, especially to China and the Gulf states.

In 2020, Fodor’s placed Barcelona on its ‘No List’ for the first time, doing so again in 2023 and 2025. But this has not served to lessen tourist numbers, which continue to grow year after year despite the physical limitation of having Europe’s highest urban density. Indeed, anti-tourism graffiti and demonstrations have themselves become highly sought Instagram backgrounds.

Tourism’s ability to capitalise on anti-tourism surely makes it the ultimate form of capitalism. Perhaps this explains why young graduates from the city’s four architecture schools have been eschewing touristic architecture in favour of housing for some time now, resulting today in a wave of innovatively constructed cooperative and social housing projects that centre on livability, not visitability. Hopefully, these fascinating new residential buildings will not be museum-ised for visual enjoyment by tourists any time soon.

La ciutat, com a espai construït, ha de ser creguda i creïble. Els seus ciutadans han de creure que existeix i que té una identitat, i aquesta identitat ha d’inspirar-los i reflectir qui són. Altrament, el màxim a què pot aspirar és a convertir-se en un museu al servei dels visitants o, en el pitjor dels casos, en un cementiri per als locals.