[Originally published in Bauwelt 15.2025]

The new training tower recently completed at Barcelona’s Vall d’Hebron fire station, designed by local architect Carles Enrich, plays a dual role within its neighborhood. It is at once a state-of-the-art training facility for firefighters as well as an urban landmark in a peripheral area of the city characterized largely by a mix of high-rise modernist housing blocks, mid-rise historical row housing, and low-rise self-built houses.

The idea of creating urban landmarks in anonymous suburban areas of Barcelona responds to an urban planning imperative adopted in the 1980s, when the city was preparing to host the 1992 Olympic Games, of “restoring the historical city center and monumentalizing the periphery.” Indeed, the neighborhood of Vall d’Hebron, which overlooks Barcelona and the Mediterranean Sea beyond from a high vantage point on the slopes of the Collserola mountain range, was designated in an urban plan by Joan Busquets to become not only one of a dozen new “Areas of New Centrality” in Barcelona, but also one of its four Olympic venues. Hence new sport facilities, transportation infrastructure and public spaces were built in addition to a large hospital complex, university faculties, a municipal market, and the very fire station to which this training tower was recently added.

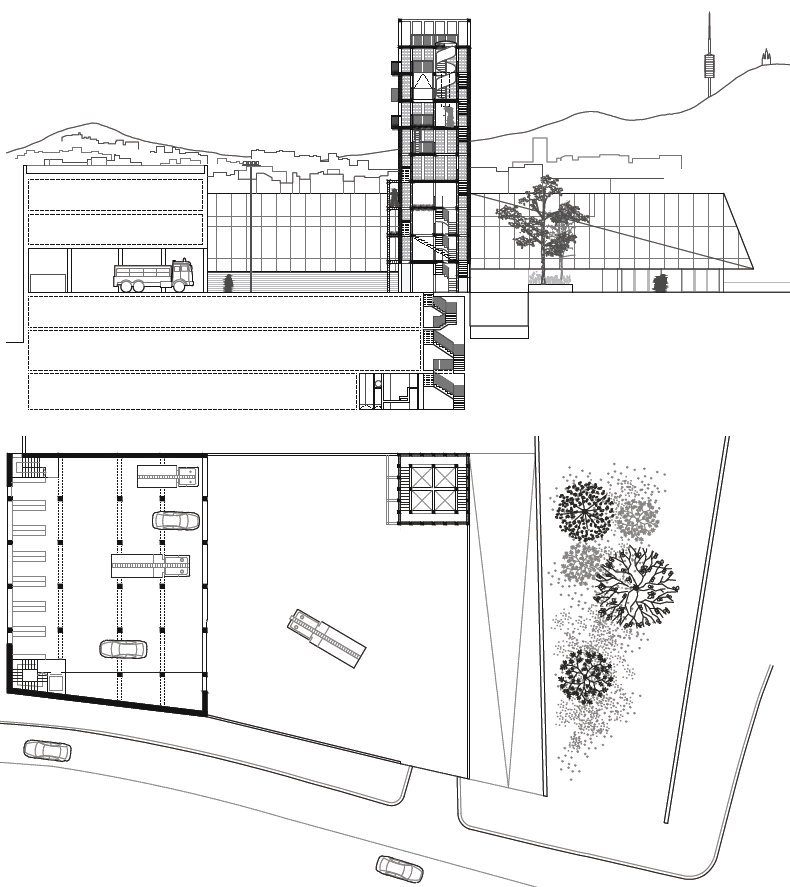

The tower is a free-standing, nine-story high raw concrete and brick structure. It is situated at a corner of the fire station’s grounds, directly across a forecourt from the firefighters’ quarters and garage. One of the tower’s edges abuts the terrain of a large municipal market, from which it is separated only by a narrow sunken laneway, while the other edge borders a ramp that descends to a vast underground parking garage situated beneath both the fire station forecourt as well as the market facility. By virtue of its proximity to its neighbor, the tower appears –architecturally– to belong to the municipal market more than to the fire station, effectively signaling this highly frequented public facility from afar. The only thing missing: a large clock at the very top.

The raw, indeed brutalist materiality of the tower contrasts sharply with both the white-enameled metal roof of the market and the dark grey compact laminate panels of the fire station building, asserting an autonomy that adds further to the ambiguity surrounding exactly which municipal facility the tower belongs to. Despite all these urban complexities, the tower is moreover deceptively simple in its outward appearance, thereby demonstrating that an urban landmark need not be “iconic” to function as such.

Used for rescue and firefighting exercises in which different sorts of emergency scenarios are simulated in a controlled setting, the tower reproduces in size and materials an array of architectural elements commonly found throughout Barcelona: stairways, balconies, party walls, and roof terraces. The two elevations facing the fire station’s forecourt simulate typical residential façades of vertical wall openings with balconies, while those abutting property lines simulate blind party walls: another common feature of Barcelona’s urban landscape. The structure –a concrete frame infilled with masonry– is equally typical throughout the city, albeit here in the more raw and unfinished state that is more typical of party walls. The masonry unit used throughout is a custom-made perforated brick orientated sideways, creating a screen that allows light and air to permeate.

As an architectural simulation of Barcelona’s modern vernacular, the tower is a sort of microcosm of the city. Indeed, at the risk of heightening the metaphor, it can be seen as an axis mundi. However, since the tower also extends below ground, where it contains an emergency exit stair for the underground parking garage, it represents a reverse axis mundi; one where hellfire and danger occur above the heavenly bliss of an egress stair designed for fire safety.

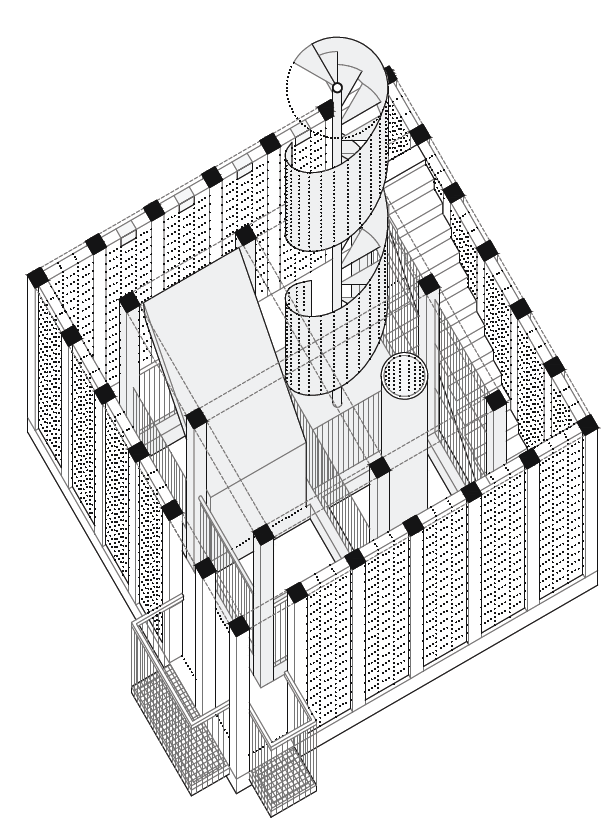

In plan, each above-ground level of the tower consists of a central space surrounded by a peripheral access gallery containing stairs; a spatial organization that permits training activities to occur simultaneously at different levels as well as inside and outside. Interior training exercises include maneuvering through a three-dimensional labyrinth of dark, smoke-filled rooms while exterior exercises involve rescues from balconies using ladders or rappelling from the roof. In one particular exercise conducted here, firefighters had to rescue dummies out of a car suspended vertically from one of the balconies.

The tower is, then, effectively a sort of ‘jungle gym’ or educational play structure. The idea of play is apparent in the tower’s architecture as well, where a central four-square grid in plan forms a rational frame within which contrasting geometric volumes such as a cylinder, an inclined plane, and a helicoidal stair form architectural follies of sorts. These forms are far from frivolous, however, serving to simulate different sorts of rescue situations. Yet architecturally, they nevertheless recall the formalist grid exercises of John Hejduk, the follies by Bernard Tschumi at Parc de la Villette in Paris, or the interior voids of OMA’s Très Grande Bibliothèque competition scheme. Somewhat more disturbingly, the tower is also comparable to those US and Israeli military training facilities for urban warfare that architecturally simulate typical Palestinian settlements of Gaza or the West Bank, (though not much is left of many of these places anymore). Both are robustly built facilities designed to withstand all kinds of use and abuse. The big difference: firefighters are trained to save lives, not to end them.

What is certain, in any case, is that the Vall d’Hebron fire training tower is architecturally highly layered and nuanced despite its seemingly simple outward appearance. With an interior that is restricted to professional use while the exterior is a highly public landmark, the tower performs at both the architectural and the urban scale; from the serious business of saving lives to the playful one of simulating Barcelona’s architecture.